Last week I interviewed some of the staff at Noir Caesar, an American studio that portrays black experiences through the medium of anime and manga.

I was especially interested in talking to them because what Noir Caesar is doing appears to reflect a sea change in the definition of anime, and I really liked the response that Noir Caesar’s music director, Will Brown, gave me, about the American-born music genre hip hop:

“One of my favorite hip hop DJs is in Japan and Japanese. Does that mean he’s not a real hip hop DJ because he’s in Japan? I tell people that and they start to see how silly the argument is that if something isn’t from where it originated, it’s not authentic. It’s an almost prejudiced perspective. Art is art.”

It’s a positive sentiment, but one some fans may be slow to accept. Just last year Reddit’s r/anime deleted a post about “Shelter,” an animated collaboration between artist Porter Robinson, anime studio A-1 Pictures, and Crunchyroll, claiming it was off topic. “‘Anime,’ they assert, is not a ‘style’ of illustration or animation,” Kotaku’s Cecilia Anastasio reported on the deletion. (It’s worth pointing out that after plenty of backlash, the forum reinstated the post.)

In the meantime, anime collaborations keep getting more global, and by extent, more difficult to define as purely Japanese entertainment “intended for a Japanese audience,” as r/anime states. Since 2013, when Space Dandy was simulcast for the East and West concurrently, it’s been clear that animation studios and Japan were thinking about a worldwide viewership. When director LeSean Thomas worked with Japanese student Satelight Inc on Cannon Busters, it evidenced that anime can be co-created by foreigners, too. Is fandom ready to take the next step, to accept that media created by Noir Caesar in America, can also be anime?

At about this point in the debate, which does happen more often these days, I insist with mock-seriousness that I require all anime creators to present a DNA test, proving 100% Japanese ancestry, before I will accept what they’ve created as “anime.”

To put it less glibly, I don’t believe purity is an important element in any entertainment medium. I love sequels and fanfiction, riffs and parodies. I believe that anime itself came out of a stylistic dialogue between animators in the East and West, ever since the “god of manga,” Osamu Tezuka, named Walt Disney as one of his chief inspirations. (And Disney certainly felt the same way—just look at the similarities between Tezuka’s Kimba the White Lion and The Lion King.)

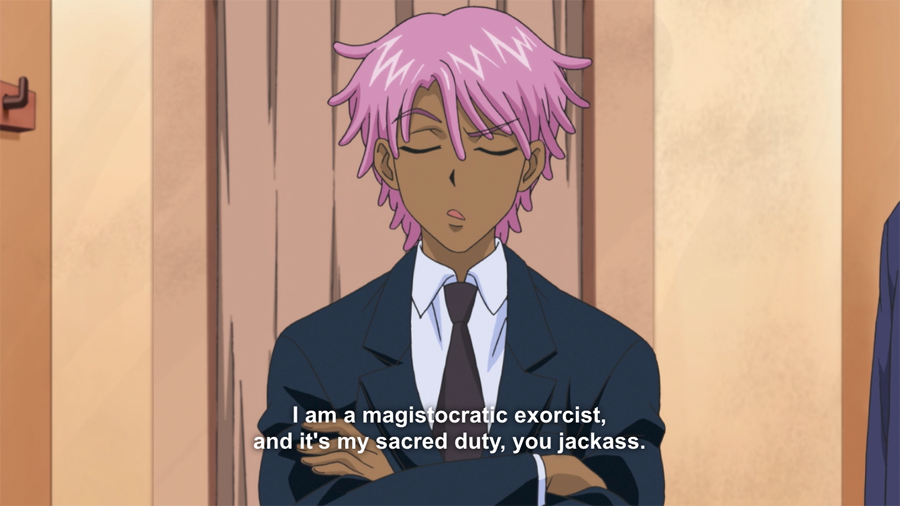

That ongoing cross-cultural dialogue brings us to the topic of this past weekend, Neo Yokio. Drawn in anime style and utilizing some of recent anime’s most well-known tropes, it is absolutely partaking in this cultural exchange solidified over the last 80 years. Like RWBY before it, it’s a US show with a distinct artistic and thematic style that is unmistakably anime.

As an anime fan of a certain age, I especially enjoy how NY is not very good. At Otakon 2011, I attended Anime News Network’s panel on anime journalism. One of the panelists said, “Anime has always been cheap and weird. But that’s part of why we like it.” This quote has stuck with me for six years, and it’s my go-to phrase for describing what it is about anime that resonates with me so deeply. It sure is weird—glaringly so—and I became a fan because it was so different than any other entertainment available to me. As for cheap, I mean tightly budgeted: the concept of sakuga (portions of animation rendered with special detail for emphasis) could have only come about because so much of the animation in anime cuts corners normally. For me, these are not simply qualities of anime, but some of the medium’s defining traits. Perhaps instead of defining anime by its creator’s or audience’s race, we can go with these cross-genre qualifiers—though even there, anime is so all-encompassing they’d be hard to nail down.

They say you get more conservative as you get older, and I’m excited to see what new spin on anime finally makes me say, “That’s NOT anime,” while the kids embrace it wholeheartedly. (I really hope that by then I can finally afford a lawn to chase them off of.) Based on the way the definition of anime has expanded, it’s likely that day will someday come. But for now, all of the characteristics that have widened the definition of anime—like increasingly diverse creators, influences, and audiences—have simply lowered the barrier to entry for anime fandom, and made it a more inclusive and accessible medium. There’s no way that’s a bad thing.

7 Comments.

K so i disagree. for many reasons here is the top couple. Lets start out with its different than most anime in aesthetic and subject matter. You say it has an anime art style and it does a bit but it is also quite different. I mean it doesn’t look like rezero! It looks more like adult swim cartoons like boondocks. so from this we can garner that yes the animation has some japanese influence but it also has some american influence. so why then are we calling anime and not a cartoon? like serious why even if you said its a 50-50 split in look between anime and cartoon well then why is it an anime and not a cartoon?

Labeling it an anime you are in effect saying its not a cartoon so in a way you are disrespecting cartoons saying its as much different from cartoons to not be a cartoon.

other point subject matter. Anime is just not known for culture satire. especially direct and modern culture critique. However western cartoons, simpsons, family guy, south park, boondocks, rick and morty. have culture critique in spades.

so like in content it is more like a cartoon and in aestetic it is more like a cartoon. why exactly are we considering it an anime?

So I disagree with YOU for several reasons. First off aesthetic does not define anime, just look at Panty and Stocking. Just because it doesn’t look like Re:Zero, or an anime similar to that means nothing at all. Also all the animation was done by not one, but two, Japanese studios. Production I.G and Studio Dean. Why make a distinction about the 50-50 split thing? You are saying it is unfair to say anime but on your logic it is unfair to say cartoon too.

As to your other point, subject matter doesn’t define it either. You say that social commentary does not occur in anime. That is just blatantly false. Tons of anime have this, be it shows that discuss the financial crisis in Japan in the ’90’s, major (traumatic) earthquakes that hit the nation, and even the Saline gas attack. If you want cultural critique, then there is that in spades too. I’ll give you that it isn’t always direct but that doesn’t mean anything at all.

Anime also means cartoon so saying one label insults the other doesn’t make sense. Long story short, you can call Neo Yokio anime. Most news outlets with authority are, you can even find it on the r/anime subreddit, it seems pretty clear-cut. You can call it a cartoon too, doesn’t really matter in a global world, both are right.

I agree, thanks for the article was an interesting read :)

[…] Orsini of Otaku Journalist asks the age old question – what is anime? Is it defined by where is was created? Or by the style it’s […]

[…] at Otaku Journalist explained in a blog post why she considers Neo Yokio to be “anime”. I wouldn’t go that far but it does […]

[…] it turned out, anger had its place in my blog post last Monday. Last week’s post did incredibly well on Twitter, sparking a lot of heated discussions about cartoons. While I […]

I’m open to the argument that RWBY, Avatar, etc are anime, but I don’t like the idea of a stylistic definition of anime. There are various anime which have animation styles very different from the common stereotype of anime such as Kaiba, Ping Pong, League of the Galactic Heroes, and Kuuchuu Buranko. If we were to define anime as animated works where characters have huge eyes, strange hair colors, and exaggerated behavior/expression of one’s emotions, where does that leave Japanese animated works that do not have these things? Are they not anime? Where do we draw the line? It seems awkward to say anime is “animated works produced in Japan along with Western animation that uses certain tropes”.

Alternatively, I’m ok with the idea of just clumping cartoons together and ending it at that (the visual novel community does something like this), but the anime community has a strong enough identity that I suspect people won’t like the idea of their anime being associated with South Park or Disney movies. I’m not sure if there is really a better way to do this.