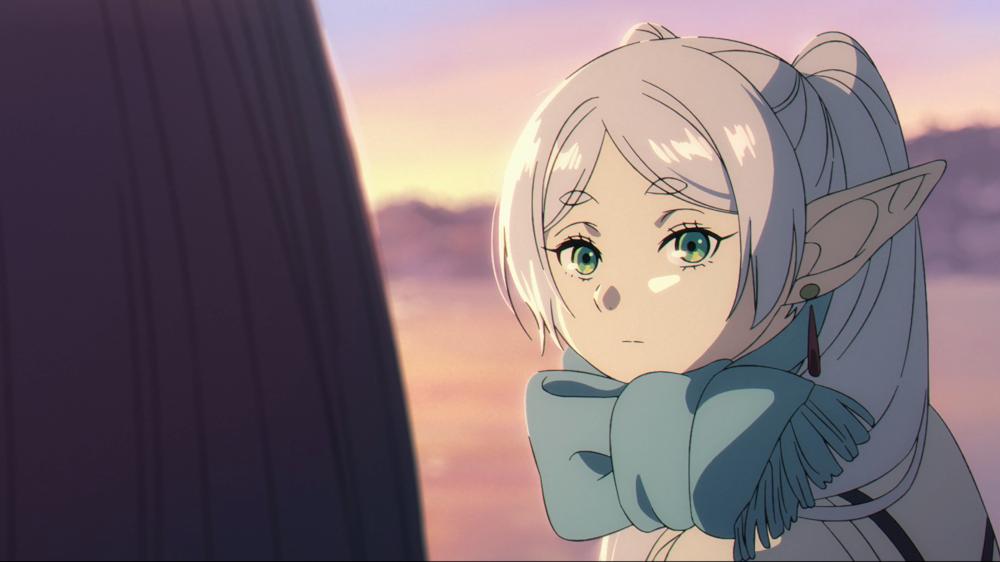

The first thing we learn about the titular character of Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End is that she isn’t human. Frieren is an elven mage with a greatly elongated lifespan; her appearance remains unchanged even after half a century has passed in the show.

Frieren thinks nothing of setting an appointment 50 years in the future, and remains stone-faced when her friend Himmel laughs at the thought—that’s the better part of a lifetime for a human like him. Frieren was fortunate that Himmel was still around to meet her for their 50-year reunion; death could have come for him at any time. He’s matured into a wizened old man by then, but Frieren doesn’t seem curious about what he’s been up to in the meantime. Fifty years is nearly a lifetime for people, but within her understanding of time, that’s barely a blip.

The human lifespan is so short that we can measure it in weeks. A fantastic, if sobering, book I read recently put this fact into stark perspective with its title: Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. “[W]e’ve been granted the mental capacities to make almost infinitely ambitious plans,” writes Oliver Burkeman, “yet practically no time at all to put them into action.” And 4,000 weeks is the best-case scenario. We aren’t even guaranteed tomorrow.

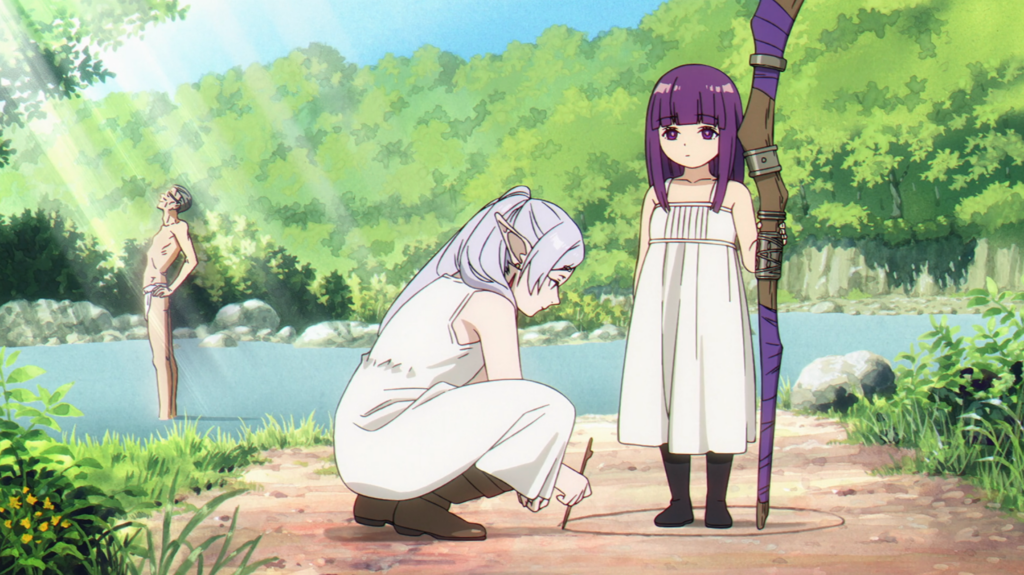

What would you do differently if you didn’t have to worry about the constraints of your own mortality? You probably wouldn’t worry so much about maximizing your productivity and making every day count. That’s why it’s no sweat for Frieren to spend 4 years training her apprentice, Fern, or to take 6 months out of her travels to scour the forest for a particular species of flower.

However, Fern is human and in a hurry. She needs to improve her magical powers now. She wants to stop dawdling over flora. When Frieren promises to stop searching for the blue moon weed flower “soon,” Fern, who has quickly become accustomed the the elven mage’s concept of scheduling, asks, “How many years is soon?”

A frustrated Fern later complains of Frieren: “She’s a mage who possesses the power to save many people. She shouldn’t spend her time searching for something that doesn’t exist.”

The emphasis is mine because I want to draw your attention to it: the idea of time as something we spend is a purely cultural one. In our modern world, we’ve collectively decided that a work day is 8 hours, regardless of whether those hours actually need to be filled with work. Before clocks, people would work when tasks required doing—and those tasks would take as long as they took. It would have been absurd for a farmer in the Middle Ages to imagine “clocking out” in the middle of the autumn harvest or prolonging it to meet an imagined hourly quota.

Clock time is so ingrained in us that it’s hard to imagine other ways of keeping time. In Saving Time, Jenny O’Dell looks to the natural world as an alternate. During the Covid-19 lockdown, she notes, people bereft of regular markers of time like commuting and weekend trips turned to observing the plants and trees growing outside their windows as the seasons changed. “What is a clock? If it’s something that ‘tells the time,’ then my branch was a clock,” she wrote.

Our society had a reckoning with time in 2020, when time seemed to develop this surreal, stretchy quality. I remember thinking how much the lockdown felt like my first maternity leave with my newborn daughter when the clock did not govern when I slept or woke, worked or played; only she did. Whether she wanted to nurse or nap, whether it was 3 AM or 3 PM, she would do what she needed to do with no regard for a clock she didn’t know how to read. Burkeman calls this “deep time” as opposed to “clock time,” and after his son was born, he noted “the otherworldliness of those first few months with a newborn: you’re dragged from clock time into deep time, whether you like it or not.”

After a lifetime in clock time, it is still hard for me to comprehend any other kind of time-keeping; the swiftest way to define it is that it’s when we are time. In deep time, time isn’t something we mark off the calendar; it’s something we exist within, and it propels us forward whether we “spend” it or “use” it or not. Of course, this is always true: even while you’re writing a to-do list about what to do with your time, you’re already doing it; time is already ticking away.

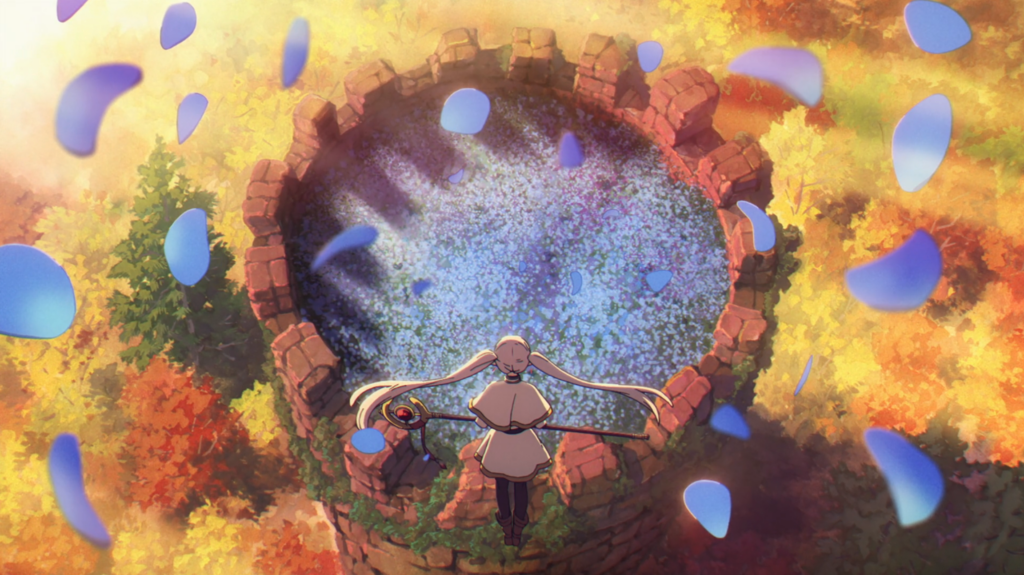

Frieren can afford to measure her time in the increment that it takes a sapling to become the most ancient tree in the forest—she’ll still be around to watch it grow. But there is a significant way that Freiren is beholden to clock time: her friends. Though she is more than a thousand years old, the humans around her will reach 100 if they are lucky, which means she only has a small window in which to get to know them. She does not seem to value her own time, but she is learning to value their time, since they won’t be around forever.

Like most humans, I don’t like to think directly about my own mortality. But after reading Four Thousand Weeks and Saving Time, I’ve begun to realize how much my acceptance or denial of my eventual death informs my every daily decision. So often I feel like time is racing by, especially as I’ve watched that same snuggly newborn I mentioned earlier turn into a quick, talkative kid in just four years. My daughter, and now my son as well, are unrecognizable from how they looked and behaved even a year ago. My daughter is as fascinated by her own growth as I am, asking if it’s her birthday again yet (her birthday is in September). She once touched her fingers to my cheek and said, “When I grow up, I want wrinkles on my face just like you, Mommy!” Unlike with Frieren, my passing lifespan shows on my face. What’s more, I try to see this as a good thing. For humans, aging is a privilege because getting old is not a guarantee.

Reminders of our mortality are everywhere. Just this past week, I’ve welcomed a new baby into my extended family and comforted a friend through the loss of a family member. Even so, I spend too much time on things that don’t really matter to me—I finish books and shows I don’t like for completion’s sake, or fritter away an hour on social media. I have more in common with Frieren’s mindset than I should, even though I don’t have her kind of time to spare.

So what do we do? Embrace our limits. As Burkeman writes in Four Thousands Weeks: “[O]nce you no longer need to convince yourself that you’ll do everything that needs doing, you’re free to focus on doing a few things that count. This works for Frieren, too; although she might not have the same mortality-imposed limits, she learns that she only has the length of a human lifespan to make memories with her friends.

Remember when Frieren reluctantly stumbled out of bed before dawn for the sunrise festival? We can understand why night owl Frieren doesn’t care about making the most of her days when she has so many of them ahead of her. But she soon learned there was only one morning she would be able to see that particular sunrise reflected in Fern’s elated face.